Artists-in-Residence | Sima Alikhani and Neda Farrahi

April 16, 2019We caught up with visual artists Alikhani and Neda Farrahi in the closing weeks of their residencies with us. Both are migrants, mothers, and painters.

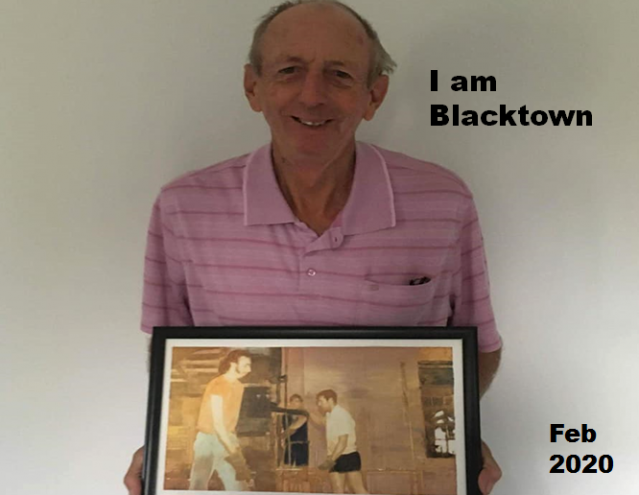

Binh Duy Ta | The Man Behind the Movement

January 31, 2019Before Binh Duy Ta begins his series of Mindful Movements workshops with Blacktown Arts, read more about the man behind the movement, and learn more about what to expect from his workshops.

IMAGinE Awards 2018 | Balik Bayan

November 26, 2018Blacktown Arts received a High Commended recognition in the 2018 Museums & Galleries NSW IMAGinE Awards for our recent project, Balik Bayan.

Insight | RIGHT HERE. RIGHT NOW.

November 6, 2018RIGHT HERE. RIGHT NOW. is for us. The people who love Blacktown and the people who loathe her. The ones that left. And the ones that stayed. This is your last chance to see her.

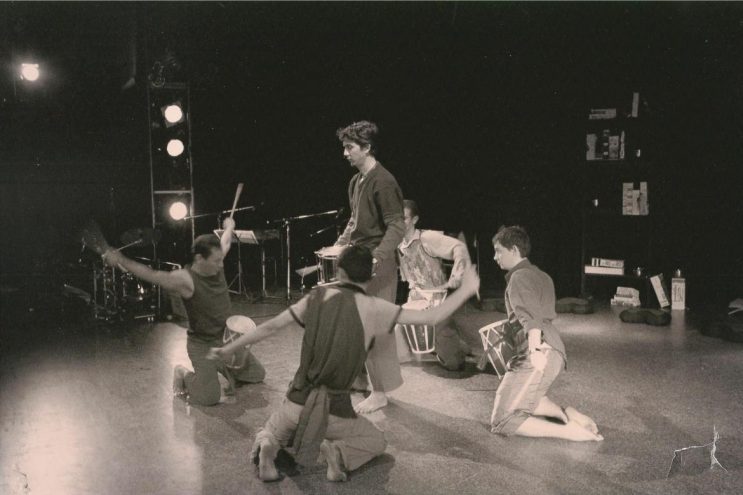

‘One Dance at a Time’ excerpt | Maryam Zahid

October 2, 2018One Dance at a Time is based on Maryam Zahid’s personal story. Maryam, an activist in Western Sydney’s Afghan community, started the online group ‘Afghan Women on the Move’.

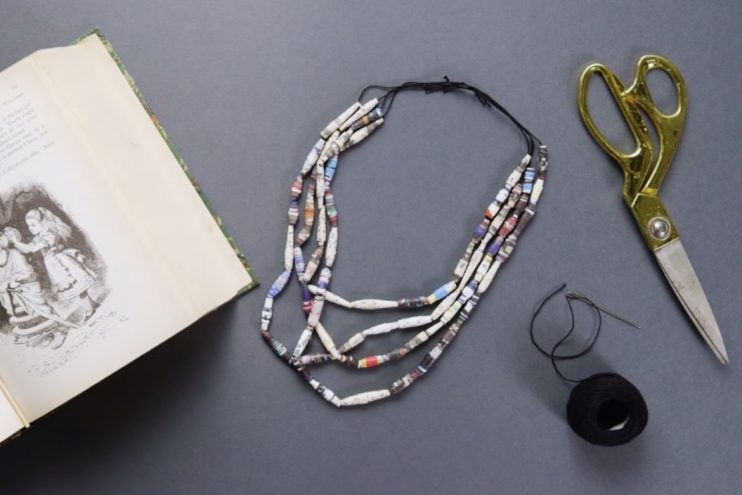

Make Art at Home | Pearls

September 28, 2018Have you ever made your own jewellery using recycled materials? Watch this fun video and make your own wearable art inspired by Simryn Gill's artwork Pearls.